In this post, we take a look at some of the names in the ONS girls’ names data from England and Wales (up through the first 300) which may surprise some people by turning up in the Middle Ages.

First up is no. 41 Imogen — historically thought to have first appeared post-1600 as a typo in a Shakespearean play, the name has an alternative history, dating back to medieval Germany.

Ancient Greek name Penelope (no. 48) came into use in England in the 16th, part of a fad for classical names. (Nickname Penny (no. 198) is more modern, though.)

No. 65 Ada has an old-fashioned feel to it — but did you know it’s roots go back at least to the 9th C in France?

Biblical names Lydia (no. 130), Leah (no. 136), Esther (no. 173), Naomi (no. 178), Rebecca (no. 186), Tabitha (no. 204), Lois (no. 215), and Rachel (no. 323) became popular amongst French, Dutch, and English Protestants in the 16th C, as did virtue names like Faith (no. 135). Interestingly, Hope (no. 139) is a virtue name that we haven’t yet found any pre-1600 examples of, though Esperanza from Latin sperantia ‘hope’ is found in 15th-16h C Spain and Italy (but not in the ONS data!)

Modern name Ottilie (no. 164) is a variant of medieval Odile, popular in France especially in the diminutive form Odelina.

No. 169 Laura first became popular after Petrarch as the poetic name for his love; it spread from Italy to France, Italy, and England over the 14th and 15th centuries.

Here’s a surprising one: Maia (no. 176). The DMNES entry is still in draft form, but we have two Low German examples from the 16th century; variant Maja (no. 192) is not an unreasonable alternative medieval spelling.

French-origin name Amy (no. 189) was popular in England from the 14th C onwards.

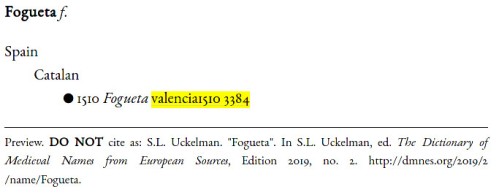

No. 196 Alba occurs in Catalan in the early 16th C.

Golden name Aurelia (no. 212) was used in Renaissance Italy. While name no. 361 Sapphire is generally interpreted as a gem name, when the medieval form Sapphira was used in 16th C England, it was more likely in reference to the New Testament character.

Did you know that Alana (no. 216) is a medieval name? It’s the Latin feminine form of Alan, and appears rarely. (Variants that add extra ls or ns or hs, such as Alannah (no. 472), Alanna (no. 650), Allana (no. 1788), Alanah (no. 1887), and Allanah (no. 3178) and compounds like Alana-Rose (no. 2901) and Alana-Rae (no. 5666) are not generally medieval.)

Nickname Effie (no. 236), usually a pet form of Euphemia (no. 4684), shows up in 16th C England (as does the full name itself) — a rare instance of an -ie or -y diminutive ending in medieval England!

Name no. 243, Talia we have examples of in 13th and 16th C Italy; there’s no entry for the name yet, as the etymological origin of the name is uncertain.

Names of classical gods and goddesses became popular in the Renaissance, including Diana (no. 275) found in both England and Italy (Diane (no. 3178) is a French form; Dianna (no. 3985) and Dyana (no. 48684) are modern forms). In general, the Latin names were preferred over the Greek — which means while we don’t have Athena (no. 239), Atene (no. 5666), Athene (no. 5666) (or the compound Athena-Rose, no. 4684) in the DMNES data, we do have Minerva (no. 2187). (The compound Diana-Elena (no. 5666) is also modern.)

Modern-day Melody (no. 312) is found in the Latin form Melodia in England during the fad for fanciful Latinate names in the 13th C. It’s during this period that we also find Amanda (no. 602).

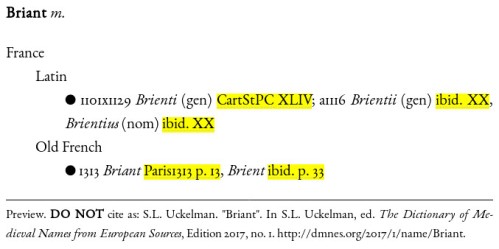

Name no. 213 Remi shows up in medieval France — but as a masculine name, not a feminine name. Similarly, Alexis (no. 323) can be found right across Europe, but only as a man’s name.

The roots of Christmas name Natalie (no. 354) go all the way back to the early Middle Ages — it shows up multiple times in the 9th C, which makes it an incredibly well-witnessed early French feminine name!

We’ll tackle names from no. 400 down in a future post.